Something Old, Something New

|

| Part 1 - Metaphors and Myths |

| Something Old, Something New |

|

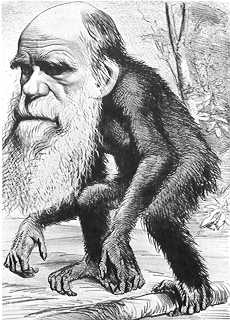

Perpetrator of a noxious blasphemy, or diligent seeker after truth? |

|

Over the last 130 years, Charles Darwin has been elevated to the highest rank the British scientific establishment. Indeed, Richard Dawkins has dubbed Darwin's evolutionary hypothesis one of the greatest ideas of all time. In short, he has become 'an authority'.

Yet the conventional accounts of Darwin's life pose as many questions as they provide answers. For example:

The information you will find in this paper has always been available to those who chose to look for it, yet it has seldom been opened up for public discussion. So why the silence?

In the words of the late Professor Loren Eiseley (of whom much more will be said in just a moment):

"The widespread popularity of the 'unconscious' theory concerning Charles Darwin can be readily explained by the fact that a cult of hero worship has developed about the great biologist ..."1

|

Darwin Myth #1: The "Unconscious Theory" This 'theory' argues that Darwin did indeed borrow material from other writers and present it as his own work - but only as a genuine oversight due to the vast amount of information which he handled in the course of his work. As we shall see, later, Darwin was scrupulous about marking all the material he wanted to reference, and was recognised as having a keen memory. So how could he manage to forget what was probably one of the most significant contributions to his thinking on evolution? That is a key element of this paper. |

Darwinism as a Religion

When Eiseley used the word "cult" I think we can safely assume that he was thinking more of a "cult of personality" rather than some kind of malign religious organisation. Yet according to Professor Stephen Jay Gould, there really is a genuinely religious dimension, of sorts, to this matter:

"... all theories [of natural selection] cite God in their support, and ... Darwin comes close to this status among evolutionary biologists ..."2

Yes he does.

The symbol below, available as a lapel badge, T-shirt logo, etc., from numerous sites online, takes the icthys (fish) design used by the early Christians - adds legs (to indicate evolution) and inserts Darwin's name.

People who approve of these changes often argue that it is merely a statement - roughly speaking, "rational science evolving from irrational superstition". This is rather less than credible, however, given the substantial number of people who are involved with science and hold conventional religious beliefs.

Whatever the symbol may have started out as, to give its origin the benefit of the doubt, one can't help suspecting that it may now have become little more than another indication of the struggle between two basic religious viewpoints - one which upholds the existence of an original creator (commonly referred to as 'God'), and one that struggles to discredit any kind of belief in a supreme being. Creationism and evolutionism.

Given that Gould made his observation back in 1978, it is worth noting that time has done nothing to moderate this view. At the turn of the century, evolutionist Michael Ruse wrote:

"Evolution is promoted by its practitioners as more than mere science. Evolution is promulgated as an ideology, a secular religion - a full-fledged alternative to Christianity, with meaning and morality. I am an ardent evolutionist and an ex-Christian, but I must admit that in this one complaint - and Mr. [sic] Gish is but one of many to make it - the literalists are absolutely right. Evolution is a religion. This was true of evolution in the beginning, and it is true of evolution still today."3

Or as Michael White put it, a couple of years later:

"Of course today, for biologists, Darwin is second only to God, and for many he may rank still higher."4

Professor Brian Goodwin throws a truly revealing light on this aspect of evolutionism - and on Darwinism in particular - when he draws our attention to the underlying metaphors used by neo-Darwinists such as Richard Dawkins:

"Dawkins' description of the Darwinian principles of evolution can be summarized as follows.

Are these metaphors beginning to look familiar?

- Organisms are constructed by groups of genes whose goal is to leave more copies of themselves. The hereditary material is basically 'selfish'.

- The inherently selfish qualities of the hereditary material are reflected in the competitive interactions between organisms that result in survival of fitter variants, generated by the more successful genes.

- Organisms are constantly trying to get better (fitter). In a mathematical/geometrical metaphor, they are always trying to climb up local peaks in a fitness landscape in order to do better than their competitors. However, this landscape keeps changing as evolution proceeds, so the struggle is endless.

- Paradoxically, humans can develop altruistic qualities that contradict their inherently selfish nature, by means of education and other cultural efforts.

Here is a very similar set.So we see that the Darwinism described by Dawkins, whose exposition has been very widely (but by no means universally) acclaimed by biologists, has its metaphorical roots in one of the deepest cultural myths, the story of the fall and redemption of humanity."5

- Humanity is born in sin; we have a base inheritance.

- Humanity is therefore condemned to a life of conflict and ...

- ... Perpetual toil

- But by faith and moral effort humanity can be saved from its fallen, selfish state

In short, in terms of its underlying metaphors, Darwinism a la Dawkins looks suspiciously akin to fundamentalist Christianity minus God. This interpretation would certainly explain Dawkins' language when he was being interviewed about a recent (January, 2006) TV series:

"Thanks to science, we now have such an exciting grasp of the answers to [profound] questions, it's a kind of blasphemy not to embrace them."6

According to the dictionary on my desk:

blasphemy ... 1 irreverent talk or treatment of a religious or sacred thing. 2 instance of this.7

Are we to believe that Dawkins didn't understand what he was saying when he made this remark? Or can we accept this as a concrete demonstration of Goodwin's interpretation of Dawkins' basically "religious" outlook?

Seven different books on Darwin sit on the table beside me as I write these words. Is it pure coincidence, I wonder, that of the seven, just one book cover shows him when he was comparatively young (40 years old). Each of the other six cover photos show the rather sad-expression, balding pate, wrinkled brow, white-hair and long white beard of Darwin in his final years - not at all unlike the figure of God the Father as depicted on the ceiling of the Cistene Chapel.

Coincidence? Or is there an element of 'brand imaging' here?

Could this be a none too subtle suggestion that it would be impudent, even verging on blasphemy, to question the life and work of such a venerable old fellow?

And if it is, why do we need to be manipulated thus?

Not all scientists in the relevant fields of study are quite so keen to deify Darwin, it must be said. But even those who are (seemingly) less than comfortable with the situation sometimes find it hard to swim against the tide. Witness the comment by geneticist C.D. Darlington:

"... there is a natural feeling (among scientists) that one of the greatest of our figures should not be dissected, at least by one of us."8

That qualifying phrase "at least" surely carries the implication that it might be entirely appropriate for someone from outside the scientific community to carry out the task.

But there is an even more compelling reason to suppose that Darwinism has moved from the scientific arena to become a quasi-religion. And that "reason" is Gregor Mendel.

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel (1822-1868)9 is most commonly referred to as the "father of genetics". Yet in practical terms he is actually the true father of the concept of evolution. That is to say, there is very little in pure Darwinism that still survives as useful material. But the fruit of Mendel's work is as valid today as it ever was. Indeed, by the 1920s Darwinism was a spent force, accepted only because no one had proposed a more viable secular alternative, rather than because of any intrinsic value.

The true foundation of the "modern synthesis", often referred to as Neo-Darwinism, fathered by Ronald (later Sir Ronald) Fisher et al, is actually Mendel's exhaustively and scientifically researched work on heredity - the real basis of genetic/evolutionary change - and not true Darwinism, which relied on such unvalidated hypotheses such as "pangenes" (on which Darwin mistakenly based his own thinking). Indeed, the very title of Fisher's ground-breaking paper, published in 1918, put the emphasis on Mendel rather than Darwin: "The Correlation Between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance".10

Why, then, are we still extolling the very limited virtues of Darwin's work, when there is someone far more deserving of our attention?

Is it simply that Darwin got there first? As we shall see, this claim is no justification, because it isn't true.

Is it because Darwin's ideas were so accurate? We've already seen, and will see time and again in this paper that this has little or no value as an explanation. Because it is also untrue.

Could it be simply because Darwin was an Englishman, and in the 19th century, Britain, and England in particular, was "top dog" across much of the globe? If so, why would the explanation still hold good in the 21st century when Britain's "Days of Empire" are 40 years or more out of date?

Could it be because Mendel's findings, and their implications, published in Moravia (far from the power centres of the Western world), were largely ignored for nearly four decades - until "re-discovered" by botanists Hugo de Vries (Dutch) and Carl Correns (German). If so, it is hard to see why this would still be a significant factor over 100 years later.

Or could it be that having Gregor Mendel as the "father of evolution" would be too much of an embarrassment to the scientific community?11 Because Gregor Mendel was a true scientist (not a rank amateur, like Darwin), but he was also an Augustinian monk when he carried out and published the results of his studies on inheritance (later promoted to abbot).

If there is any truth in the latter proposition, then clearly the public face of Darwin and Darwinism today are as much a matter of "religious" considerations as they are to do with science.

In the rest of this paper I shall investigate, in detail, the claims for Darwin's scientific knowledge, in particular the question of whether there is any real justification for his title as "the father of evolution."

[Note: A more detailed discussion of the blurring of the boundaries between science and religion, especially by so-called ultra-Darwinists, can be found in Chapter 2 of the book Alas, Poor Darwin, entitled Less Selfish than Sacred? Genes and the Religious Impulse in Evolutionary Psychology, by Professor Dorothy Nelkin.12]

Recognition of a DebtBefore continuing with this narrative, I must acknowledge my indebtedness to the late Professor Loren Eiseley.

I had been working on this subject for quite a time - a year or more - and had written the comment (at the end of my notes) that:

"It seems fair to say that Darwin's main role was as a compiler of facts rather than as an innovator in the field of evolutionist thought. But where did it all come from? His own explanation doesn't ring true."

In this way I tentatively anticipated a part of Eiseley's findings. In most other respects I was, I freely admit, as blinded by the "Darwin Myth" as anyone else.

In hindsight, as researchers often find, I can see that I actually had all of the pieces of the jigsaw in front of me - with just three exceptions. Without the final pieces I was unable to make sense of the picture I had so nearly assembled.

And then I read Professor Eiseley's collection of essays published (posthumously) under the title: Darwin and the Mysterious Mr. X. At last I had found the three crucial missing pieces. The result is this paper.

In recognition of my debt, references to sources are to Professor Eiseley's book wherever he was my first source. Original references are only given where I had already collected the relevant information before reading Eiseley's book.

By the way, just in case you've never heard of Professor Eiseley I should explain that he was the author of a number of well-respected books including The Immense Journey, The Star Thrower and The Unexpected Universe, (all still in print). He was also an academic of some standing - Benjamin Franklin Professor of Anthropology and the History of Science at the University of Pennsylvania, to be precise.

Not even the most ardent evolutionist can trash Eiseley's reputation or realistically accuse him of having a hidden creationist agenda. In consequence his book has either been ignored, or studiously misrepresented.

As Darlington rightly observed, scientists do not want Darwin or his work exposed to close scrutiny, especially not by one of their own.